A few years ago, Matt M. and I made a trip north into Virginia to hike through parts of Jefferson National Forest, including Mount Rogers, Virginia’s highest peak. Both of us agreed that this is a great region for backpacking, so this time, we tricked invited four additional friends to come with us. Today (and tomorrow and the next day), Chip B., Marques D., Brian D., Matt M., Eric S., and I would retrace (most of) the same route we took back then. (We made some minor pivots—nothing drastic.)

Day 1

We all piled into Eric S.’s van around 09:30 hrs on a Friday and headed north toward Virginia. There’s a small parking area just off of Fairwood Valley Road (VA 603), which is great if you didn’t get permits for the backpacking lot at Grayson Highlands State Park. (Not because you’re bad at planning or totally cheap! No, of course not!) We pulled in, parked, and tossed our packs on before heading just up the road—Fairwood Valley Road becomes Laurel Valley Road—where we turned left onto the Mount Rogers Trail.

Mount Rogers Trail

About 1/3 mi in, the terrain sheds its subtle uphill veneer for the protracted climb it truly is! The grade isn’t extreme, the trail isn’t overgrown or even terribly rocky, but for the next 1.5 mi or so, the Mount Rogers Trail presents practically zero chill. And when that happens, it’s totally fine to take a break so you don’t give yourself a heart attack.

I’d been concerned about how well I’d handle things: I still wasn’t sure if Grandfather Mountain—and even a moment in Shenandoah National Park—the year before were just outlier episodes or something else that I’d have to anticipate on every hike from now on. Even though we were just getting started, I was gratified to think it had just been a one-off undiagnosed illness during the former case and not enough calories during the latter.

Anyway, not long after starting the Mount Rogers Trail, we passed a sign letting us know we had entered the Lewis Fork Wilderness. Established on the eastern slope of Mount Rogers, this land, once host to numerous homesteads, was designated in 1984 through the Virginia Wilderness Act. I couldn’t find any definitive explanation for why it’s called the Lewis Fork Wilderness: likely the name of former settlers, or maybe an early surveyor. (All of this wilderness—or very nearly all of it—is part of Jefferson National Forest.)

East of us, about on the other side of the Scales (we’ll get there tomorrow), is another wilderness: the Little Wilson Creek Wilderness. If you watched the video, you probably noticed my less-than-smooth dub in the intro. I must have had the Little Wilson Creek Wilderness on my mind—even though we ended up never entering it on this trip!

Appalachian & Virginia Highlands Horse Trails

After the first 2.2 mi (from the parking area), the Mount Rogers Trail relents somewhat and offers a gentler ascent through (predominantly) southern Appalachian beech forest. At just about 4 mi, the Mount Rogers Trail merges with the Appalachian Trail (AT), and it’s pretty smooth for the next 9/10 mi. That’s when we took a minor detour onto the Virginia Highlands Horse Trail (VHHT)—I can’t seem to keep myself from calling it a bridle trail in the video. Maybe it doesn’t matter?

There’s something of a “layer” of uniquely shaped trees between the woods and the bald over which the VHHT runs. Apparently, there’s a fancy word for such a transitional gradient between two different ecological regions like this: ecotone. Neat!

These trees are likely beech and yellow birch (the flowers are likely white wood aster or white snakeroot). Because of these higher elevations and the absence of a “shield” against the wind and weather, they grow gnarled and stunted, something called krummholz-form, an effect that keeps even older trees from reaching their full potential despite possibly having lived for decades. (Krummholz is another new word—German for “crooked wood.” Nice!)

Sometimes people refer to these trees as “fairy trees” or “gnome trees,” and walking through them so close to sunset, I can appreciate why! There’s an odd beauty in their misshapen trunks and branches, especially when framed with the early autumn remnants of these white flowers (clearer in the first photo above).

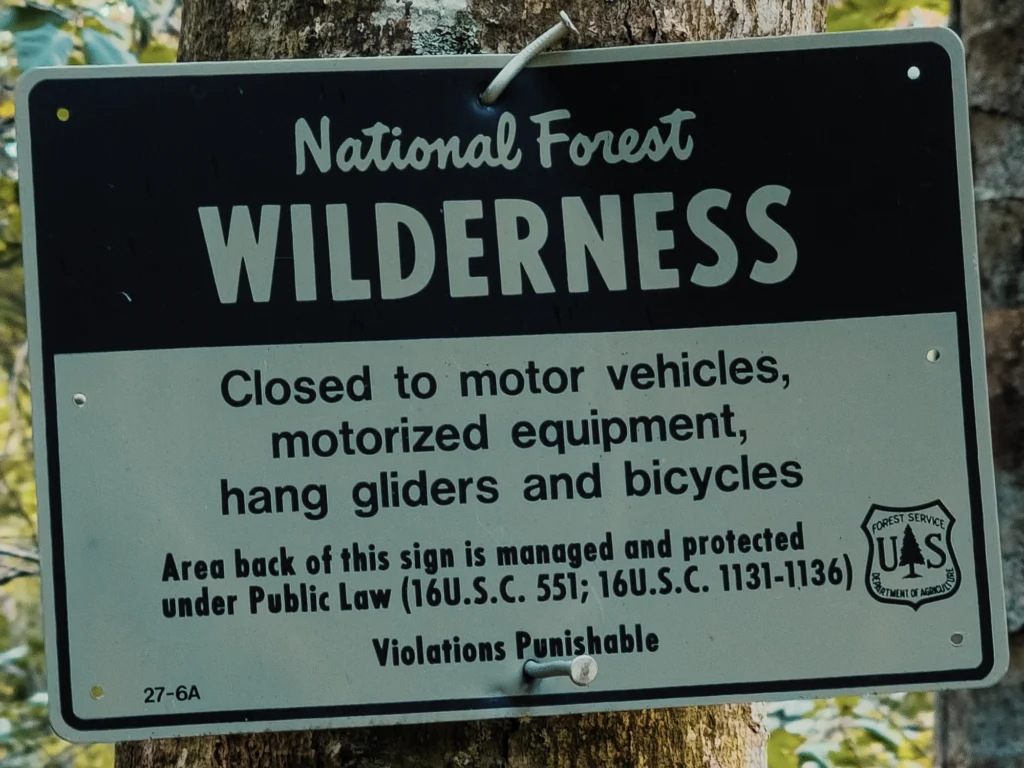

It’s barely visible, but there’s a small sign at the edge of the bald. Here’s what it says:

It’s a little hard to read, given how faded it is. (Probably from the same environment that caused the krummholz-form growth throughout this ecotone—all right, all right: I’ll try to be a little less obnoxious with these new words! No promises.) Anyway, here’s another, more legible instance of that sign:

I suppose your average scofflaw could probably ride a bike up here, maybe even an ATV, but…hang gliders? That seems like an awful lot of effort for, well, I don’t know: there’s a downward slope into the balds and valley below the VHHT, but I wouldn’t have thought it sufficient for hang gliding. Although I don’t know anything about hang gliding, so there’s that. Still, this sign always gets a chuckle out of me. Yes, I’m easily amused. Also: violations punishable…by what?!

Along the edge of the bald here, there are old fence posts, quite possibly remnants from the homesteading era (18th & 19th centuries), when settlers established farms and logging operations in the region. Such endeavors, particularly logging and livestock grazing, took their toll on land: first the forests, hastened by the chestnut blight that swept the eastern U.S. during the 1920s; then the soil and streams, at which point the federal government got involved.

We followed the VHHT, rejoined the AT, and after about 1 mi total, we reached the Mount Rogers Spur Trail. The sun was already low in the sky, and even though the spur is only about 1/2 mi, we passed it and decided to return and hike to Mount Rogers’ summit in the morning. Actually, the sun wasn’t just low in the sky—it was gone! I had enough twilight to navigate the trail, but not much else. In the video, I’m shining an LED fill light right into my own eyes: beyond that, you start to get a sense of how dark it had already become!

From the base of the Mount Rogers Spur Trail, we hiked another 4/10 mi to 1/2 mi just past the Thomas Knob Shelter. In the dark, we set up our tents while others got a campfire going. It was mid- to late September, so not truly cold at night, but cool enough that a roaring fire felt like the best idea! After supper, I think some of us might have sat around the fire, enjoying its warmth and conversation—with each other, not the fire—for a little while until the coals burned themselves from bright orange to deep reddish-brown to black. Today we hiked something like 6.5 mi: tomorrow we’d hike even more. Time for bed.

Day 2

Since I’d done such a great job describing Mount Rogers to the other guys, only Brian D. wanted to backtrack to the spur trail. (Matt M. had been there before: he knew what he was missing.) The air had a touch of chill when I stepped out of my tent: enough that I decided to wear my jacket. Now ready, we stepped out of the semi-wooded tent site onto the AT. Mount Rogers was west of us, but the sun was still creeping toward the horizon toward the east:

This sunrise has to be one of my favorites, maybe even more so than the one I saw from Mount Sterling in the Smokies. For a minute or two, we watched the sky change colors while cloud inversions swirled below us, then we headed toward the spur trail.

Mount Rogers Spur Trail & Mount Rogers

We moved quickly, partly because of the cold and partly because we still had a long day in the opposite direction—and neither of us had eaten breakfast yet! Within a few minutes, we reached the base of the Mount Rogers Spur Trail (the elevation here stays right around 5,400 ft). I’d warned Brian D.—and the others!—that Mount Rogers’ summit is completely treed-in. There are no views. That acknowledged, we continued hiking.

The first part of the spur trail feels fairly wide; that is, it’s not choked with trees, but after a few hundred feet, the woods start closing in. About halfway up, the scattered hardwoods give way to spruce-fir forest more common in the northeast than here. Portions of the trail took us across large boulders until eventually we reached the summit.

I don’t have any medium- or wide-angle photos from the top of Mount Rogers, but I did snag a couple of the geodetic survey markers up here. We found two, but I’ve read there might be others.

I’m sure I’m selling Mount Rogers to whomever’s reading this about as well as I sold it to the others. Maybe you’re wondering, “why add another 2 mi to the day to look at…trees and rocks?” That’s probably a fair question. Mount Rogers is Virginia’s highest summit, topping out around 5,729 ft. Named for William Barton Rogers, Virginia’s first state geologist (and founder of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), who conducted surveys of the region in the 1830s–1840s, Mount Rogers rests squarely within the Jefferson National Forest (designated in 1936) and the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area (designated 1966).

By this time the sun had fully risen, and I’m pretty sure both of us were getting hungry, so we turned around and hiked the mile back to camp. Along the way, the sun highlighted the threads in this spider web right beside the AT:

Cool!

Another (SOBO) hiker saw me squatting to get this photo and asked what I was looking at. I showed him the web, and I don’t know if he thought it was cool too, or if he was just being polite as he continued on his way.

Back at camp, the others had a fire going and had already begun packing up their tents. I think I was boiling water for oatmeal when I noticed the sunlight filtering through the trees, catching in the smoke from our fire:

I think crepuscular rays like this are super neat! Glad I was able to snap this photo before the smoke dissipated.

After breakfast, and after making sure our fire was out, we finished packing up and continued NOBO on the AT. We started much, much later than we should have, especially considering the 10.6 mi in our original route, but I’ll admit: I enjoyed the leisurely morning!

From just east of the Thomas Knob Shelter (named after Thomas Knob, in turn named after David Thomas, first president of the Mount Rogers Appalachian Trail Club [MRATC] and his wife Nerine), the AT starts out fairly level with only minor changes in elevation. Our next stop was just about 1 mi away: Pine Mountain.

Pine Mountain & Wilburn Ridge

Somewhere along this mile, there’s a great view of Pine Mountain framed by trees on either side. There’s also a marker here bearing a number: NOBO AT through-hikers, congratulate yourself for completing 500 mi of the AT!

I like this little peek through the trees because it gives you an opportunity to glimpse your next reward. Not long after this preview, we reached the spur trail for the summit of Pine Mountain (5,526 ft). There’s usually lots of pony, uh, evidence along this 400 ft trail (maybe a little less), but dodge all that for spectacular views of the Virginia highlands! (I’ll discuss the ponies later in this post!)

Up here, we’re just outside of the Lewis Fork Wilderness (although still within Jefferson National Forest), so I launched the drone to capture some aerial views. Stunning stuff.

After that, we hiked down the spur trail and back to the AT. On our way toward Wilburn Ridge, I thought I heard something mooing. Then someone said something about a cow! Sure enough, resting in the scrub lay a red-and-white longhorn calf! Around 2012, the U.S. Forest Service introduced feral cattle to the region to help maintain the highland balds.

Not quite 1/3 mi down the trail from Pine Mountain, there’s a split: veer right and hike across the highest points of Wilburn Ridge via the Wilburn Ridge Trail, or continue following the AT and hike along the side of the ridge. Given our collective pace, most guys opted to stay on the AT. Brian D. and I decided to drop our packs and hike just to the “top” of Wilburn Ridge, which only added 1/4 mi.

Wilburn Ridge Trail runs about 7/10 mi parallel to the AT, but at a higher elevation. The highest elevation on Wilburn Ridge is the same as Pine Mountain: about 5,526 ft. This ridge is named after an old cattleman named Johnny Wilburn who grazed his livestock here and knew this land well. Matt M. and I hiked the Wilburn Ridge Trail the last time we were here, and I wouldn’t have called it backpack-friendly with all the narrow paths and thick branches. That 1/8 mi up, however, didn’t seem too bad—although maybe I’m only saying that because I didn’t have my pack?

After a quick scramble to the top (this place was crowded!), Brian D. and I hiked back down, retrieved our packs, and eventually caught up with the other guys.

Grayson Highlands State Park & Massie Gap

One of the reasons for the crowds on Wilburn Ridge probably stems from its proximity to Grayson Highlands State Park. It’s just 8/10 mi from Wilburn Ridge to the boundary of the park, and we even saw families with small children hiking the trails near here.

From the gate into the park, we hiked another 8/10 mi to Massie Gap (still part of the park), passing riders on horseback as well as tons of other hikers. While deciding whether to hike straight up the hill from Massie Gap or continue down the AT a bit, someone complimented me on my Moxie hat. Turns out he’d spent some time in Maine—which makes sense, because almost no one not from New England knows what the heck Moxie is! (It’s a delicious carbonated beverage that in no way tastes like, as my dad would say, “root beer with cigarette ashes.” Nope, it doesn’t taste like that at all.)

We ended up hiking down the AT and searching for a social spur to the rocks above Massie Gap. We should have just hiked straight up the grassy path instead! At last, after getting our arms and legs scraped and our packs almost torn from our backs, we got there, and even more than at Wilburn Ridge, these rocks proved to be quite popular with park visitors. I waited for the people sitting atop the highest rock to move on, then I claimed that spot for myself while the other guys settled for slightly lower rocks. Bright sun and gentle breezes made this place an ideal location for lunch.

Massie Gap (roughly 4,660 ft) gets its name from the Massie family, one of the last remaining homesteading families in this region (into the 1950s and 1960s). Homesteaders, livestock drovers, and likely others would have used this gap as a simpler route between neighboring elevations. It’s bounded by Wilburn Ridge to the north and Haw Orchard Mountain to the south.

Quebec Branch, Wise Shelter, Big Wilson Creek, & Wilson Creek Trail

After Massie Gap (via the grassy path we should have taken in the first place), we hiked about 9/10 mi to the Quebec Branch, where we stopped for a while to filter water. Oh, right: while I was packing up my stuff from the morning, a few people took all our water containers to the source just below the Thomas Knob Shelter. According to them, hardly any water was flowing, and there was quite a line forming, so they only filtered about a liter, liter and a half per person.

I wondered why this stream is called the Quebec Branch—we’re a long way from Canada! I couldn’t find a definitive answer, but maybe it gets its name from veterans of the French & Indian or even the Revolutionary Wars? Maybe something about it reminded someone of a cold Canadian morning? Or maybe it’s the surname of someone who lived or homesteaded in this region? Regardless, I’m thankful it was here—and that it was flowing!

As we were leaving the Quebec Branch, Brian D. reminded us how much he loves beans.

Now that we had water for the rest of the day (and for rehydrating supper), we hiked about another 8/10 mi to the Wise Shelter. This shelter, part of the AT shelter system, is still within Grayson Highlands State Park. There are signs on either side of it reminding would-be-tenters that there is no tent camping allowed! Like most places around here, it’s likely that the Wise Shelter gets its name from a local family from back in the day, but I couldn’t confirm that. It was likely built in the 1970s or 1980s, and today the MRATC maintains it.

About 1/10 mi up the trail past the Wise Shelter, we crossed over Big Wilson Creek, which was a probable water source for homesteaders—like the Wilburns, the Massies, and others—and their livestock.

In the first paragraph, I said we changed our route. A little more than 2/10 mi past Big Wilson Creek, we shaved about 1.4 mi from our intended distance, forsaking the AT for the Wilson Creek Trail, which cut the distance from 2.6 mi to 1.2 mi (from the start of the Wilson Creek Trail). Big Wilson and Wilson Creeks get their name from a hapless young surveyor, who, back in 1749, drowned while mapping the border between Virginia and North Carolina.

Feral ponies

The first third of the Wilson Creek Trail is relatively easy, but after that, there’s a protracted 1/2 mi uphill—an old road, or maybe just a wider horse trail—that gets your lungs screaming. I don’t know at what point it started raining, but somewhere after that nasty climb, the sky opened up and let us have it. After quickly donning rain jackets and covering our packs, we continued hiking.

While it was still raining, we came across a small herd of feral Wilburn Ridge ponies!

In the 1970s, the Wilburn Ridge Pony Association (WRPA) introduced feral ponies to the region to help maintain the balds. They graze the area for shrubs and seedlings to help prevent open areas from reverting to forest. While largely hands-off, the WRPA and other volunteers take steps to ensure the herd remains healthy. Every year, they host an auction to help keep its population manageable.

When I first learned about these ponies, I wondered what happened to them during the winter. Turns out they’re well-adapted to the harsher elements of Virginia highlands winters! They grow thicker coats, and they seem to have a knack for locating forage beneath the snow. Of course, the WRPA does keep an eye on things for the rare occurrence in which the ponies might need extra help, but generally speaking, cold and snow don’t seem to bother them too much.

Not long after encountering the ponies, the rain stopped. Not long after that, we reached the end of the Wilson Creek Trail at the Scales.

The Scales

Right around 2.3 mi from the Quebec Branch (and still within the Jefferson National Forest), there’s a relatively flat, well-watered field where cattlemen used to bring their livestock for an annual auction every spring and summer. They weighed their animals with mechanical scales installed between the late 1800s and early 1900s, hence the name. Sometimes buyers from as far as Tennessee used to travel to the Scales to participate in those auctions.

Modern roads and improvements in livestock transportation gradually saw the Scales (around 4,600 ft) decline in favor as a working landscape toward something of a backcountry relic. By the time these regions were designated wildernesses (1984), virtually nothing of the once-lively enterprise remained except and open field and maybe a few scattered concrete pads and dilapidated fence posts.

That said, there is a fence surrounding the majority portion of the field. There’s even a couple of privies and portable toilets (do not go in there!) near one corner. Sometimes it’s possible to see ponies—and even longhorns—grazing nearby. Today, the Scales seemed almost crowded with car campers: this place is accessible via Pine Mountain Road (FS 613), but your vehicle had better have the right ground clearance!

By this time of day, the shadows were growing longer, so we didn’t stick around. From the Scales, we took the Crest Trail back into Jefferson National Forest, choosing its higher elevation (and slightly straighter route) instead of the AT. One the way up, something flickered in my peripheral vision. I turned to look and saw a few more ponies grazing off to my left!

Looking over all my photos of these ponies, I realize that every last one of them has its face in the grass! I wonder if they’re binging before colder weather sets in? Or maybe they’re just hungry all the time.

Crest Trail, Appalachian Trail (again), & the Old Orchard Shelter

We took the Crest Trail for about 9/10 mi until we joined back up with the AT. I lost track of the other guys—back at the Scales I had to, uh, see a man about a horse—but when I caught up, they were about a hundred feet off the trail under some trees. I couldn’t figure out what they were doing until one of them shouted, “That cow is not friendly!”

At first I didn’t see what they were talking about, but as I continued toward them, I saw a large longhorn grazing between us. I did not get any photos—or video footage—of this guy, but later, I learned that he’d been on the trail when the other guys approached him unawares. From what they described, it sounds like Matt M. got a little too close (not on purpose—he’s not that dumb!) and the longhorn reared back and chased them into the trees! I’m probably saying this because I wasn’t there, but man, I wish I’d been there!

Nearly 9/10 mi from the Scales, we turned right off of the Crest Trail onto the AT again. We almost missed it! The Crest Trail is well-worn and rutted through here, but the path toward the AT begins on close-cropped grass that leaves almost no indication that it’s even a trail. (I guess that longhorn was doing his job!)

We followed the AT into thicker woods for about 1.7 mi until we reached the Old Orchard Shelter. Chip B. and I were the first two to get here, so we scouted a site with room for all of us and started setting up. With my tent pitched and staked, I sat down on a log next to the fire pit and just enjoyed the environment:

We sat around the fire for a while. I remember telling Matt M. that this time around, it felt like someone stretched out the trail compared to a few years back! I’m sure getting older has nothing to do with it. Not a thing. He (Matt M.) was smart enough to take a quick nap before supper; me, I just sat there. I’m sure if I’d tried to take a nap, I would have stayed in my tent until morning.

Eventually, I boiled water for supper, and after a few minutes of conversation, I went to bed.

Day 3

We got a much better start on Day 3 than Day 2! I don’t remember what time, but well before 10:00 hrs or whatever it was the day before. After a quick breakfast, I finished packing up my stuff—including the makeshift clothesline I hung for my rain jacket and socks, and we crossed over the Old Orchard Trail that intersects the AT just above our campsite. In about 1.5 mi, we’d reach the Fairwood Valley Road—but not the end of our hike.

Most of the trail between the Old Orchard Shelter and VA 603 runs downhill. With a good night’s rest, a belly full of breakfast, and a crisp, not-quite-autumn morning, I felt pretty good! Much like the first part of the Mount Rogers Trail, we were surrounded by southern Appalachian hardwood forest, the spruce and fir having thinned about above us some time ago.

Fairwood Valley Trail

We crossed Fairwood Valley Road, which, after 80 ft and a sharp left, put us on the Fairwood Valley Trail (FVT). There are quite a few horse camps around here, and this trail is intended more for horses than humans it seems. It’s much wider, and even though we’re not really gaining (or losing) any real elevation, there are moments where the incline changes quickly.

It’s probable that the “original” FVT started out as (or parallels) a drover route local cattlemen might have used when moving their livestock into the highlands, or maybe an old logging trail: the woods around here were selectively logged during the 1900s, mostly chestnut (likely pre-blight), oak, and poplar.

Part of the trail opens up with meadows (and VA 603) on our left. Hiking through this meadow, we crossed paths with at least four cows. Bulls. At least one of them was a bull, but none of us stuck around long enough to get an accurate count! These guys (and gals) were standing no more than 15 ft to 25 ft away from us, staring without blinking as we passed by.

No one got trampled, so that’s a win.

There’s 1.8 mi between where we joined the FVT and the parking area. Over this distance, we crossed Fox Creek, completed one last uphill push, and finally reached Eric S.’s van and the end of this adventure.

This region is great for backpacking. Various ecological zones, expansive views, and (sometimes), feral ponies! I’m thankful the six of us had the opportunity to hike through a portion of it. There are bunch of other trails that crisscross Jefferson National Forest and the Lewis Fork and Little Wilson Creek Wildernesses, but I think the views from Pine Mountain and Wilburn Ridge—even those rocks above Massie Gap—are hard to beat.

Catch the whole adventure on YouTube! Please consider subscribing (if you haven’t already). Thanks for stopping by!

Pingback Hiking the Profile and Grandfather Trails at Grandfather Mountain State Park (NC)