I originally planned to return to the Smokies and hike from Newfound Gap to Fontana Dam, but Hurricane Helene intervened. While it’s possible we might have been able to make it west across the state, we opted not to chance it and pivoted toward someplace north instead. That’s how we ended up in Shenandoah National Park.

I haven’t been to many national parks, but compared to the few I have visited, Shenandoah seems a lot…longer and skinnier. That made planning a loop route a bit of a challenge, but I came up with…something. Our initial itinerary included four days and three nights, but we pivoted (again!) and knocked it down to three days.

The meaning and etymology of the name Shenandoah continues to engender debate. Some claim it means daughter-of-the-stars or river-through-spruce, while another believes it means ancient river people via an old Gaelic dialect! Still others suggest it’s an Iroquoian name that became associated with the river and the valley.

Another interesting thing about Shenandoah National Park: roughly 40% of is designated wilderness. I don’t think I realized that while researching this route—I’m not sure how I missed it! The major campsites, visitor centers, and Skyline Drive are not wilderness (obviously), but many of the trails we hiked during this trip are.

Big Meadows Campground

Shenandoah is a little less than 80 mi west-southwest from Washington, D.C., which somehow escaped my notice when trying to cobble something together with an abbreviated amount of planning time. I think we must have headed north around noon, maybe a little before lunchtime. Our destination: Big Meadows Campground, not too far off of Skyline Drive (the “greatest single feature” of Shenandoah National Park). We rolled in with maybe a couple of hours before the sun set and, after waiting for two or three whitetail deer (all does) to leave our spot, we set up camp. Matt M. made me and Eric S. his version of asado, including homemade chimichurri. Delicious. While exploring the campground, I saw yet another deer—a buck this time—just meandering about:

He didn’t seem to notice us—or if he did, he didn’t seem to care. Good for him. We made a campfire, and after it burned down, we turned in for the night.

Day 1

I didn’t want to get out of my tent in the morning: it was cold! When I did get up, I noticed frost on my truck bed’s tonneau cover. Fortunately, the Harry F. Byrd, Sr. Visitor Center, which we’d passed on the way in, sold warmer hats and gloves. I bought a hat, and I think the other guys bought hats and gloves. Better equipped, we drove to the Big Meadows Amphitheater parking area, parked, and started down Lewis Spring Falls Trail.

Lewis Spring Falls Trail

The first 1.1 mi of the Lewis Spring Falls Trail (LSFT) dropped us about 750 vertical ft. Not a bad way to start the day! I started the trail pretty bundled up, but before we reached Lewis Spring Falls, I’d rolled up my pantlegs and shed an upper layer or two. From Big Meadows to Lewis Springs Falls, we passed through a mix of hardwoods and evergreens: oak, mountain laurel, and eastern hemlock.

Within another 2/10 mi to 3/10 mi, we reached Lewis Spring Falls, Shenandoah’s 4th-tallest falls (81 ft). It’s difficult to adequately photograph the entire run, since the longer portion hides behind a rock outcropping, and in the fall (when we visited), water levels are lower than during the summer. Still, I snapped a photo of the shorter, upper portion. (I was experimenting with shutter priority with my phone’s camera at the waterfalls on this trip. Clearly, I have yet to master the settings!)

Over the 7/10 mi or so, we gained about 440 vertical ft. The last 250 ft of the LSFT are the tail end of a dirt road: in fact, blissfully ignorant, I walked past our turn onto the Appalachian Trail, onto Lewis Spring Pumphouse Rd. Fortunately, Matt M. and Eric S. got my attention before I ended up back in North Carolina!

Appalachian Trail

We followed the Appalachian Trail (AT) for about 6/10 mi until we reached Tanners Ridge Cemetery, which wasn’t part of Shenandoah National Park until 2022. The oldest headstone here dates back to 1850, I think. I couldn’t find much information about Tanners Ridge Cemetery, but it stands out just before you cross Tanners Ridge Fire Rd.

We hiked through reasonably flat terrain over the next 1.1 mi, passing the Mill Prong Trailhead parking area and crossing over Skyline Drive. We remained on the AT for roughly 2.4 mi longer—crossing Hazeltop (roughly 3,800 ft)—until we turned left onto the Laurel Prong Trail. (We’d be back on the AT before we finished this trip.)

Laurel Prong, Cat Knob, & Jones Mountain Trails

The Laurel Prong Trail runs east for about a mile before it takes a hard left toward the north: it’s a relatively mild trail through the same forest mix as before. Instead of taking it north at Laurel Gap (around 3,238 ft), however, we kept straight (in a generally southeastern direction) and took the Cat Knob Trail for a little more than 1/2 mi.

I had gotten ahead of the other guys, so after crossing over Cat Knob (just under 3,700 ft), I waited for a minute, because I had a suggestion.

This day had felt slow since the morning. We’d only hiked about 7.5 mi, but it felt like we should have made better progress at this hour of the day. My original route had us taking the Jones Mountain Trail (south) past Bear Church Rock and the Jones Mountain Cabin before turning north via the Staunton River Trail. When Matt M. and Eric S. arrived at the junction between the Cat Knob Trail and the Jones Mountain Trail, I suggested we head north on the Jones Mountain Trail and skip about 6.7 mi. (The Jones Mountain Trail comes to an odd, upturned “point” where it meets the Cat Knob Trail.)

I don’t think either of them seemed to mind, and so we planned to camp near the base of Fork Mountain for that night, and we’d figure out Night 2…later.

Since we modified our route, we only had about a mile more to go for Day 1. The Jones Mountain Trail just touches Fork Mountain Fire Rd before “rebounding” toward the north as the Fork Mountain Trail. We set up camp just off the road and very close to “The Sag,” just slightly southeast of us. (The Sag is a geographic depression between neighboring peaks and not part of Shenandoah: we were right on the park’s edge here.) By now the sun started to disappear, so after a quick supper, we went to bed.

Day 2

I’ll admit it: I didn’t have “wake up to the sounds and smells of a diesel engine” on my Shenandoah bingo card! (I don’t have a Shenandoah bingo card. I don’t think they’re real). We’d discussed venturing to the summit of Fork Mountain (around 3.840 ft), but it’s a hike up a fire road, and from what I’d read, it’s occupied by communications equipment and affords no views. Probably just as well we skipped it: I think my “alarm clock” for that morning was a dump truck hauling away demolition debris.

After a quick breakfast and a rough refactor of our goal for the day, we packed up and headed down the Fork Mountain Trail—away from Fork Mountain.

Fork Mountain & Laurel Prong Horse Trails

I didn’t mention it yet, but with leaves just starting to fall, we had a hard time noticing all the rocks underfoot. I think most of these trails were really just loose stones buried under bright yellow leaves. Not great for the feet and ankles! We hiked down the Fork Mountain Trail for just about 1.2 mi, then turned right onto the Laurel Prong Horse Trail.

Other than the “invisible” rocks, these trails are a pleasant walk: mostly downhill based on our point of origin, dropping maybe 700 ft over that 1.8 mi. If there weren’t any leaf litter obscuring things, we might have been better able to gauge where the worst of the rocks lay hidden.

When we reached the Laurel Prong, we filtered water, then discovered we’d need to take our shoes off to ford the river. I don’t know how warm or cold the Laurel Prong is normally, but in early October, it was…tingly. Once across, we hiked the Laurel Prong Horse Trail for another 6/10 mi until we reached Camp Hoover.

Camp Hoover

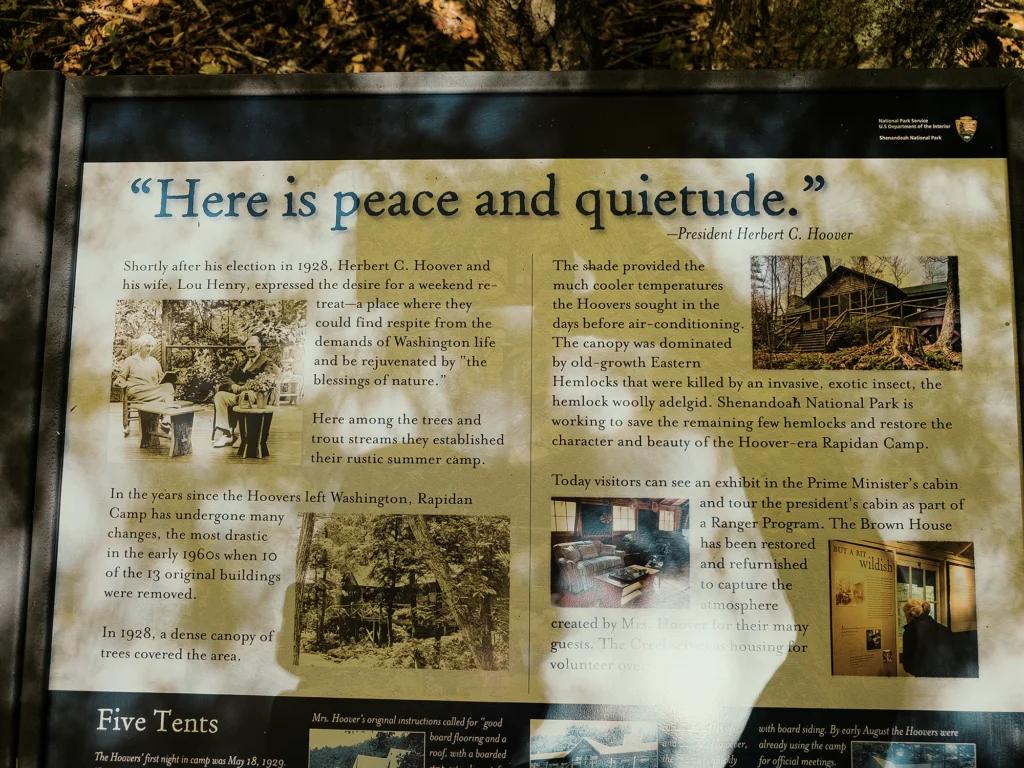

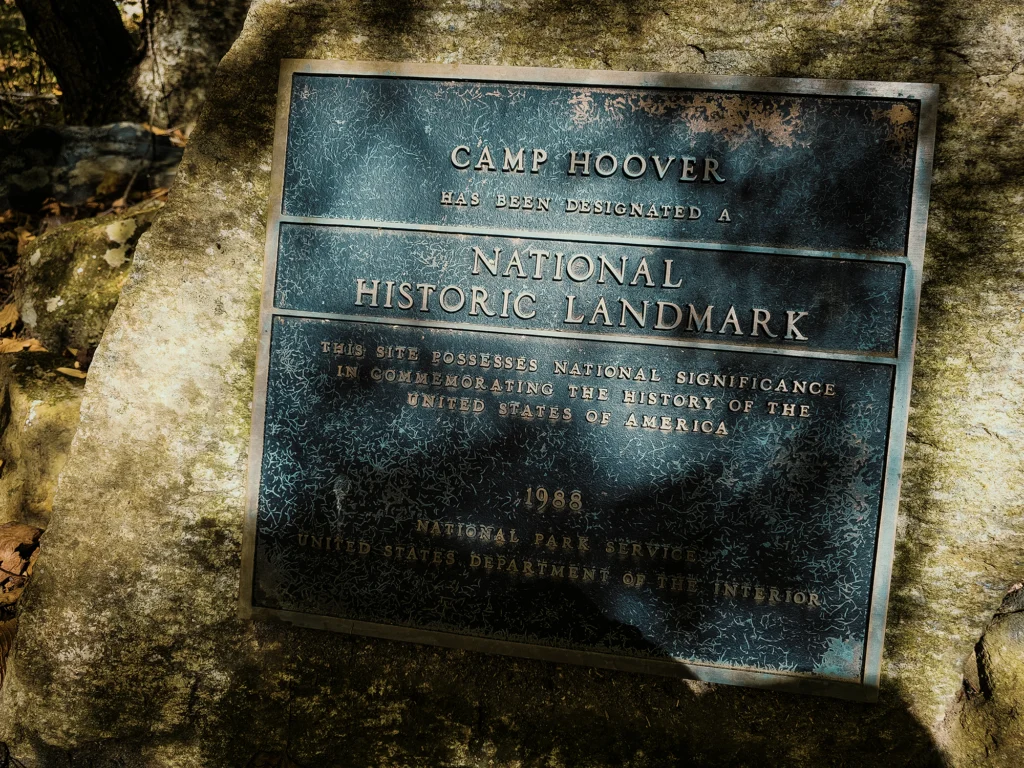

Most presidents prior to Herbert Hoover, America’s 31st, hailed from the eastern United States. Hoover grew up in Iowa and worked as a mining engineer in California, and during those years, he developed an appreciation for remote accommodations. Even in the late 1920s, early 1930s, one needed to get beyond the boundaries of D.C. to find such places. Hoover directed his secretary to find such a spot with the following conditions: 1) within 100 mi of D.C., 2) higher than 2,500 ft above sea level (he thought that would keep the mosquitoes away!), and 3) near a good trout stream.

Virginia Senator Harry Byrd and a man named William Carson (I mention him earlier in the video for Day 1) persuaded Hoover (or his secretary) to consider the headwaters of the Rapidan River, where the Mill Prong and Laurel Prong converge. In fact, the state of Virginia offered to present the land to Hoover as a gift, but he purchased it with his personal funds. He and his wife, Lou, then built Rapidan Camp.

Hoover used to host foreign dignitaries here: one building (now a museum) is called the Prime Minister’s Cabin, since Hoover hosted Winston Churchill at Rapidan during World War II. (The Hoovers stayed in the larger structure called The Brown House.)

Hoover only served one term, but he offered Rapidan Camp to future presidents for use as a retreat away from the faster pace of D.C. He donated the land to the federal government for inclusion in Shenandoah National Park, then still under development. At some date between the 1940s and 1950s, the site was renamed Camp Hoover.

I intentionally structured our route to include Camp Hoover, but I had no idea how interesting it would prove to be! Our timing wasn’t great though: with a little additional planning, we might have been able to score a tour through the Brown House. Instead, we explored the Prime Minister’s Cabin, the converging rivers, and the remnants of old chimneys from demolished buildings.

Mill Prong Horse Trail, Rapidan Fire Rd, & Stony Mountain Trail

After an extended visit at Camp Hoover, we headed north on the Mill Prong Horse Trail (MPHT). Just shy of 1/2 mi north from there, we crossed the Mill Prong just below Big Rock Falls. I’m not sure where it ranks against the other waterfalls in Shenandoah National Park, but Big Rock Falls drops maybe…12 ft. I’ll give whoever named it points for accuracy: on an otherwise slick-looking rock face, there’s a large boulder altering the water’s flow. And that’s it.

About 9/10 mi north of Camp Hoover, the MPHT turns sharply right—the Mill Prong Trail continues straight. We stayed on the MPHT for another 9/10 mi until we reached the Rapidan Fire Rd (RFR).

We hiked walked just shy of 1.7 mi along the RFR, stopping for lunch along the way. The cold morning was long gone, replaced with a much warmer afternoon. The RFR follows a mostly downward slant (if you’re heading generally northwest like we were) until it takes a hairpin turn around a sharp right. This point is also where we left the RFR and got onto the Stony Mountain Trail (SMT).

The SMT runs north for about 1.1 mi and serves as a connector between the Rapidan and Rose River Fire Rds. Its overall slope is also downhill, dropping from roughly 3,000 ft to nearly 2,560 ft. After 8/10 mi on the Rose River Fire Rd (RRFR), we reached another hairpin turn (left this time) onto the Rose River Loop Trail—bur first, despite the late hour, we stopped to admire Dark Hollow Falls.

Dark Hollow Falls

Maybe I watch too many horror movies or play too many video games, but the name Dark Hollow Falls just sounds like it belongs in one or the other—or both! Dark Hollow Falls consists of an upper and a lower section. There’s a short trail toward the upper section that we didn’t have time to complete, but we did spend a few minutes at the lower section.

Dark Hollow Falls is one of the most-visited waterfalls in Shenandoah National Park (in part because it’s so close to Skyline Drive). Its overall drop height is 70 ft. After getting a few photos here, we continued on the Rose River Loop Trail for just over 1.1 mi, I think, until we almost ran out of daylight. We hopped off the trail near a relatively flat spot between the Hogcamp Branch and the Rose River.

As we were setting up camp, I noticed someone had used this site prior: they’d left a small cairn at the root of a tree. Neat.

I don’t think we could have built a fire here, even though I would have greatly appreciated one. Once the sun goes down, it gets cold fast! Instead, we just heated up our suppers via canister stove, talked for a little bit, then went to bed.

Day 3

One of the reasons we changed our route was to get home a day earlier. That meant today we’d have to hike just over 10 mi, I think. Normally on multiday trips, I try to make the last day much shorter—that 6+ mi on the last day of the Tricorner Loop is about as high as I prefer to go. Oh well—I’ve got no one but myself to blame.

Rose River Loop Trail, Rose River Falls, & Skyland Big Meadows Horse Trail

Just over 1/4 mi from…wherever it was we camped, we reached Rose River Falls. At the base of these falls is a “swimming hole.” Being October, I didn’t see anyone swimming in it, although I was sorely tempted! But that 1/4 mi hike hadn’t quite driven the morning chill out of my bones, so I settled for a photo before moving on.

The next 3.8 mi started out relatively even, but after about 2.7 mi, we started uphill again. Oh, right: about 7/10 mi from Rose River Falls, we left the Rose River Loop Trail for the Skyland Big Meadows Horse Trail. I’d like to offer a colorful description of this portion of the trail—of all the trails we’d hiked up to this point—but the truth is it’s hard to differentiate one trail from another! Some are narrower, some are wider—the horse trails, mostly, but the majority were rocky paths overlaid with leaves. That’s not to say it wasn’t beautiful scenery, because it was. I don’t think a lot of people hike Shenandoah in loops: I’d guess it’s mostly through- or section-hikers for the AT, and probably day hikers or families with small children for some of the other points of interest, especially since so many of those are relatively close to Skyline Drive.

Skyline Drive

Completing the Skyland Big Meadows Horse Trail, we reached the parking lot for the Upper Hawksbill Trailhead, just across the road from Skyline Drive. Earlier, I described Shenandoah as long and thin, and that’s in large part because the designers intended Skyline Drive—which was originally going to be called the Hoover Highway—to be the backbone of the park, offering views of the Shenandoah Valley to the west and views of Virginia’s piedmont to the east.

Skyline drive construction started in 1932, with help from local farmers and apple-pickers looking for work. In 1933, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), brand-spanking-new, contributed work hours as well.

Up until the 1950s, chestnut guardrails defined the edges of Skyline Drive, but by that time their rotting remains were carted off and never replaced—since the 1900s, the fungus that causes chestnut blight arrived with Japanese chestnut trees and quickly decimated American chestnut populations.

Hawksbill Mountain

Right before we started up the 1 mi trail to the summit of Hawksbill Mountain, I started feeling weak, almost like I felt earlier at Grandfather Mountain. I don’t know why, but after eating what would have been Day 4’s lunch, I felt a lot better, and we continued hiking.

Hawksbill is Shenandoah National Park’s highest peak, standing just about 4,050 ft tall. Its northern face includes an approximate 2,500 ft drop—the greatest elevation change in the park. (There are no trails up Hawksbill’s north face.) There are stands of balsam trees up here too—species more at home in colder, northern climates.

We ate lunch up here (“second lunch” for me!) and enjoyed the breeze. Someone’s super awesome dog hung around us for a while. Nice! After too short a time, however, we needed to head down. We still needed to reach the truck before dark.

Salamander & Appalachian Trails

People day hiking Hawksbill probably take the Upper Hawksbill Trail back to their vehicles. Obviously, that wasn’t an option for us! Not quite 2/10 mi from the summit, there’s a right turn onto the Salamander Trail, a 6/10 mi connector that provides access to the AT. Just over 1/4 mi after that, we reached the spur for the Rock Spring Hut Shelter (part of the AT shelter system). It’s a steep downhill, but Eric S. wanted to make sure he had enough water. Once finished, we hiked back up that spur and continued generally southwest for about another 1.5 mi.

I think this is the site of an overlook with views across the valley toward the George Washington National Forest and the Massanutten Range in the distant west-northwest. There were a few other hikers out here when we arrived. I tried not to disturb them while I snapped a few photos:

By now the shadows were definitely getting longer, so we needed to move more quickly over the last 2 mi. Within a few hundred feet of Big Meadows Campground, we startled at least three or four whitetail deer. I think we startled three, but a fourth was less skittish than the others: she barely moved as we continued up the trail. Voices from campsites just beyond the edge of the woods filtered through the trees surrounding us, and still she remained unfazed (although she did keep an eye on us).

Maybe 6/10 mi after crossing paths with those deer, we reached the Lewis Spring Falls Trail spur that led back to the Big Meadows Amphitheater and the truck! We dropped our packs and snagged a drink from whatever was left in the cooler from three days earlier. I think I got a grapefruit Spindrift, but I don’t remember. Doesn’t matter.

Exhausted, we pulled into the Harry F. Byrd, Sr. Visitor Center to change clothes, then settled in for the five-hour drive toward home.

I like Shenandoah National Park, but I don’t think I did it right. I think next time (if there is one), I’ll pick a campground (or two, or three, depending on how many nights) and set up the tent there, then pack it all away and leave it in the truck and day hike to various points of interest. Some of those hikes will be longer than others, but I think that approach lets you experience more things without having to hump 40+ lbs. through the woods! Something I’ll have to think about for sure.

Oh—that Sheetz Freak from the morning of Day 1? Eric S. wedged him in a strap on his pack. He was there when we entered the woods that morning, but he was gone by the time we exited those woods three days later. Maybe a bobcat or a coyote or something found him and used him for a chew toy? Probably no one will ever know.

Catch the whole adventure on YouTube! Please consider subscribing (if you haven’t already). Thanks for stopping by!

Pingback Backpacking in Jefferson National Forest (Mount Rogers, Wilburn Ridge, the Scales, and more) (VA)